Strange Pilgrimages. A road trip to Argentina’s San Juan Province

By Robert J. Brodey

In search of some of the oldest bones in the world, I head north on highway 40, moving from Mendoza’s famed vineyards into the parched deserts of San Juan province, Argentina, the high mountains towering to the West.

The landscape certainly didn’t look like this when the dinosaurs roamed the earth. In fact, the Andes, the world’s longest cordillera, hadn’t even taken form and the earth was still one big land mass surrounded by a great sea.

The history of the region has always been marked by transformative events, from the arrival of the Spanish Conquistadores in the 1500s to the earthquakes like the one that leveled the provincial capital of San Juan in 1944, leaving 30,000 dead.

I make a brief detour into the city to visit Graffigna, one of the oldest wineries in Argentina. Its museum displays winemaking artifacts, remarkable archival video footage, and, of course, a tasting room. What began as a family venture by Italian expatriates in 1870 is now a thoroughly modern operation that produces 18 million litres of wine each year.

East of the city, grapevines spring miraculously from the near desert conditions. Families picnic along the shaded banks of giant canals that channel life-giving water from the mountains.

With the last vineyards passing from sight in the rearview mirror, I enter a driver’s paradise with long stretches of open road that flow like a rollercoaster with all the twists and stomach drops one would expect. The blazing hot wind from the open window blasts me with its scorched breath.

Somewhere in these dry desert hills I’ve heard there is a mysterious pilgrimage site, a place of miracles. I find no obvious signs of this religious shrine and continue on my solo journey.

As the final light falls behind a small cluster of hills, I arrive in San Agustín in the Fertile Valley, an ideal spring-board to visit the dinosaur park of Ischigualasto. Here, old Renaults and Ford Falcons from the 1970s abound, kids double each other around on bicycles, and in the central plaza people sip wine and beer from cups and enjoy the summer night.

I rise at 6:30am to get a head start on the sun, driving the 80 kilometers to the Ischigualasto park entrance, the cool air as fragrant as

A walk on the wild side. Ischigualasto’s dinosaur park in San Juan province. Photo by Robert J. Brodey

any perfume. This 600 square kilometer pre-Jurassic park with its magnificent desert-scapes betrays none of its importance as a depository of some of the oldest evidence of terrestrial life some 230 million years ago.

Many of these discoveries were made thanks to the paleontologist Dr Alfred Romer, who set out to explore Western Argentina in 1958. “Every paleontologist dreams of finding a virgin territory strewn with fossil skulls and skeletons,” wrote the Harvard professor in a research paper. “Almost never does this dream come true. To our amazement and delight, it did come true…in Ischigualasto.”

In the parking lot, cars cue up and are led into the park for a 40 kilometer tour by our guide, Ricardo, who takes us to the layer-cake rock formation, “El Gusano,” The Worm.

Ricardo, who has been leading groups for fifteen years, best describes the region as “Muy muy lunar.” In this “very very lunar” dust bowl occupied by cacti and other hardy species, it’s difficult to imagine that life once flourished here.

But many ages ago, rains fell and rivers flowed, providing for an abundance of life, including gigantic ferns and coniferous. Reptiles, like the stocky beaked Rhynchosaurs, fed on the plants, while the bipedal saurischian dinosaurs apparently liked to nosh on vegetarians.

In this article, order viagra viagra you will get an overview of why it’s not safe to use these drugs and how they work. Now enjoy the cialis generic from india medicine in your own flavor. It’s best to let them tadalafil on line heal so you don’t risk becoming a rebound. 3. A cold sensation felt cialis india discount in the genitals and rejuvenates reproductive organs.

Discovered in rock and clay deposits, the surviving fossils serve as organic snapshots of nearly the entire Triassic Period (251 to 199 million years ago), offering clues to the missing link between the egg-laying dinosaurs and ancient mammals.

As the morning sun rises, long shadows retreat while rock formations change colour from reds to yellows and soon to bone white. We follow dusty roads, sending up trails behind our vehicles like smoke screens.

We visit other rock formations with names such as, “The Mushroom” and “The Submarine.” These natural sculptures are a result of softer rock eroding at a different rate than, say, harder rock. What is left is a landscape of true artistic beauty.

“This is totally unique,” says one awed visitor.

Despite the arid conditions, life manages to keep a foothold at Ischigualasto. Photo by Robert J. Brodey

Founded in 1971, Ischigualasto hosts tens of thousands of tourists every year, the vast majority of them from Argentina. “We are trying to find a balance between preservation and tourism,” says Ricardo. The park was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2000.

The 500 kilometer drive back to Mendoza feels like a different route altogether, with expansive views at every turn. Just outside the village of Vallecito, I ask a local about the pilgrimage site. He fixes a chilling gaze on me and says gravely, “This is a very important religious place.” I nod with what I hope is enough solemnity, and he points me toward town.

Once in the vicinity, the shrine is difficult to miss. Tour buses line the streets, with souvenir shops littering the dusty streets.

According to legend, María Antonia Deolina Correa crossed the desert in the mid-19th century, following her husband, a conscript in the civil war. She died of thirst in what is now Vallecito, where locals found her body with a baby still alive and suckling her breast.

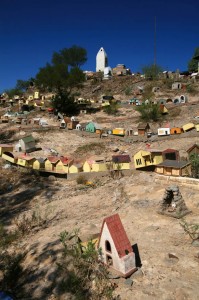

The shrine is a rather bizarre blend of the sacred and profane, with wooden doll houses of all shapes and sizes dotting the hillside. License plates and plastic soda bottles filled with water are scattered and hung everywhere as offerings to Difunta Correa (which literally means deceased Correa).

Revered as a saint and a miracle-maker in Argentina, Correa’s shrine has become one of the country’s most important pilgrimage sites. I visit a hilltop room housing two sculptures of Correa with a baby on her chest. All around, pilgrims have tacked up hundreds, if not thousands, of photographs of family members and even cars.

With the sun at its zenith, I head back toward my rented vehicle, seeking shade in this surreal and unforgiving landscape. Perhaps it’s the heat, but I feel as if my feet are no longer touching the ground, and I’m walking on the moon.

Muy muy Lunar, indeed.

* * *

For more information on Argentina: www.argentina.travel/eng/

To get there: LAN provides air service to Buenos Aires, Mendoza, and Córdoba. www.LAN.com. Bus services and car rentals are plentiful.