Living Under Siege: A Writer’s Return to the Land of Israel

Robert J. Brodey

In the shadow of Damascus Gate, a group of Israeli soldiers stop a Palestinian man for questioning. The Arab Quarter of old Jerusalem, for the time, seems oblivious to the incident. Ancient women carrying burlap bags on their heads pass the souks filled with candy, clothes, and toy guns. Young men and boys with three-wheeled carts loaded with the day’s produce, fly through the narrow streets. Four modest looking Muslim girls, whose heads are covered with fine cream-coloured silk, stare bewildered at the woman in a tight neon-green mini-skirt strutting through the market.

A raised voice from the midst of the small crowd collected around the soldiers now gains the attention of other market-goers. Sensing an event in the making, more people gather at the crisis point to look on. This only aggravates the situation. Tension builds on Al-Wad Road.

The crowd, like a noose, draws tighter around the dispute. The soldiers, with machine guns and combat helmets slung from their Kevlar vests, seem nervous and pace in and out of the mob. Suddenly two Palestinians flare up, shouting at each other. The men become the centre point around which all else revolves. Then one man gives way to his anger and head butts the other. The victim seems shocked and touches his forehead, examining his fingers for blood. Immediately, several soldiers pull out wooden batons amid the pushing and shouting and shove the agitated crowds back. Another soldier grows enraged and hauls the Palestinian aggressor to the corner of a shop stall. Staring at each other with contempt, they exchange angry words. The soldier snaps and head-butts the Palestinian. At any moment, the situation may explode. A soldier in wrap-around shades anxiously radios for help. Soon, reinforcements arrive.

Then, what has taken a handful of minutes to build, dissipates almost immediately. An army commander breaks into the heart of the conflict and with an unwavering look orders his men to withdraw, taking with them one of the Palestinians at the centre of the controversy.

* * *

By the Rivers of Babylon we sat down and wept when we remembered Zion.

Psalm 137

Since Israel’s birth fifty years ago, crisis and controversy have followed it every step of its painful growth. Arguably, this slender territory at the cross-roads of Western and Eastern history, is the most disputed piece of real estate in the world. Despite the constant threat of war, though, the Jewish Diaspora that had scattered to the four corners of the earth–from India to Australia and Uruguay to Ethiopia–after the destruction of the Second Temple in A.D. 70, continues to return to Israel, if only to visit. Of the many faces of the Diaspora crowding the Ben Gurion airport on October 26, 1998, Dad and I are just two among them.

It is our first time here, and it took some serious deliberation to finally decide to make the journey. Both of us have strong reservations about Israeli policies, particularly concerning the mistreatment of Palestinians. Our plan is to travel the country for three weeks. We decide to save Jerusalem for the end. Something tells me I will need to prepare myself for it.

It seems fitting that the first significant site we visit in Israel is the museum of the Diaspora, at the University of Tel Aviv. As we enter the gate we are met by angry picketers. A student strike has just begun, protesting the raising of tuition fees.

The Museum begins with a visual history of the rise of modern anti-Semitism in Europe in the 1920s and 30s. In display cases, German propaganda posters bolster the image of the Volk as strong and white and characterize the Jews as large-nosed rats invading the country. Soon words take life through action, and the displays show the hatred manifested in all-out persecution and codified in Law.

Then we descend further. An area details the development of Jewish culture in the Middle East. We trace the steps of the Jewish dispersion and how each community developed its own unique characteristics in such places as Yemen, Poland, Spain, Russia, and America. Models detail the varying styles of synagogues through-out the world.

One cannot speak of Judaism without speaking of Zakhor–memory. Jewish survival has always depended on remembering collective events, from Abraham’s near sacrifice of Isiah on the mount, through the expulsion of the Jews in Spain in 1492, the Holocaust, to the Yom Kippur War in 1973. Ritual, too, plays its part to evoke memory. The crushing of a glass at Jewish weddings, for instance, recalls the destruction of the First and Second Temple.

What quickly becomes apparent as I wander through the assembled histories is the constant repetition of intolerance and violence. Documents recounting the horror of Cossack massacres in 1648-9 read little differently then the atrocities committed in Palestine by the Romans or in Germany by the Nazis. One story tells of a Jewish woman who escaped the Inquisition, only to be hunted down in Mexico in the 1600s and burned alive with her children as punishment for eluding the authorities in Spain.

But the museum’s visual history doesn’t end with the imagery of the victimized Jew. It finishes with Theodor Herzl’s dream of a Jewish state and the accounts of the Aliyah’s, the returning shiploads of Diaspora through the 1920s, 30s, and 40s. So in that way, the museum is not simply here to retell a story. It stands to justify the existence of the state, itself.

* * *

There on the willow-trees we hung up our harps, for there those who carried us off demanded music and singing, and our captors called on us to be merry: ‘Sing us one of the songs of Zion.’

Psalm 137

The sun descends quickly as Dad and I stand on the hillside overlooking Syria from 77 Battlefield, the site of an important tank offensive in the Six Day War of 1967. In the darkness, we drive along desolate fields until we stumble onto the Kibbutz, Merom Golan, further down the road.

After some hesitation, the manager agrees to let us stay. The burly man clad in overalls shows us our bungalow. It takes no time for dad to engage the kibbutznik in a lengthy discussion about Israeli politics. “For every two Israelis,” he quotes the oft repeated saying, “there are four opinions.” Dad asks about the tensions between the religious and secular Jews. Immediately, he complains bitterly about the Orthodox who are exempt from mandatory military service. “The religious,” he says mockingly, “believe they are soldiers, dying every day fighting for the souls through prayer.”

At first glance it seems strange that Kibbutzim communities are huddled together behind walls, barbed wire, and guard posts. Then it dawns on me that nothing has really changed in three thousand years. Everyone who has ever settled in the Fertile Crescent (with perhaps the exception of the Bedouins and Druze) always chose the most strategic locations to live and defend themselves.

The kibbutz were really designed as outposts to claim, develop, and defend the land. Merom Golan, itself, was built within months of the Israeli annexation of the Golan Heights. When land is occupied by civilians it suddenly becomes a moral issue if these communities are threatened. This seems particularly true in the West Bank where Jewish settlers lay claim to contentious areas by building homes. Then the military state has an “obligation” to defend these Jewish homes and can justify a military presence in areas predominately inhabited by Arabs.

Since the inception of Kibbutzim in the 1920s, much has changed in the way they are run. These fortified settlements, with their strong socialist ideals, have seen a shift toward money-making enterprises, which make them financially viable. The abandoned and rusted guard towers stand like ghosts watching over the gates that are now always open. Kibbutz still, however, carry some of the spirit of peace and reconciliation of their early founders. Under a staircase at Merom Golan Kibbutz is a shrine with candles and messages of prayer for Yitzhak Rabin, the Prime Minister slain this day, November 4, in 1995 by a Jewish gunman. For many, including myself, his assassination was the first introduction to the most divisive crisis threatening Israel — the fight between the Orthodox and Secular Jews.

* * *

How could we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land? If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither away; let my tongue cling to the roof of my mouth if I do not remember you, If I do not set Jerusalem above my highest joy.

Psalm 137.

All week, I have felt myself travelling through a dream, a surreal detachment from life around me. Perhaps, I’ve been suffering from jet lag, or maybe I’m just overwhelmed by the newness of everything. Each morning I would struggle to get out of bed before nine, my body heavy and aching. Things seemed meaningless. Who cares that the civilizations of Caeserea or Acco were stacked on top of each other –Phoenician, Jewish, Crusader, Arab. I barely noticed I was in the mountain town of Sfat, the home of Jewish Kabbala, the mystical esoteric teachings. It is for this reason, my father laughs when I inform him I will be getting up at six a.m. to watch the sun rise over Syria.

Motivation has definitely been a problem until now, but I want to see the Golan Heights in the right light. Before 6am. I awake, dress, and get into the car. The sun has already begun its ascent, bathing Mt. Hermon to the north in a blaze of colour. At this instant, I fall in love with Israel. I am elated, singing at the top of my lungs as I bomb down the highway, stopping by the side of the road to take pictures. I have found what I’ve been missing all this time. Connection. Inspiration. I had been stumbling through the days unsure of what I was looking for. Now I have found my reason. The crisp cold air reminds me that I’m alive.

The stony earth, like dry bones, remains exposed to the bleaching heat of the sun. My father and I drive south along highway 98 until we reach an old dirt road that follows the UN patrolled Disengagement Zone with Syria. We pass several enormous steel windmills that churn wind into electricity for the national grid. On either side, stone fences and bunkers mark the old battle lines between the Syrian and Israeli armies during the ‘67 and ‘73 wars. Signs posted on the barbed wire warn of the hazard of Syrian land mines left from the war.

We drive slowly, listening to the bottom of the car scrape along the enormous folds in the road left by the weight of patrolling tanks. Attack helicopters storm by overhead, while soldiers, in the distance, roam around on manoeuvres. It takes almost two hours to cover the twenty kilometres of pitted and chew-up roads before we rejoin the main highway leading down toward the Sea of Galilee.

It is by good fortune we find ourselves in Ma’ale Gamla, at the home of Noga and Shugi and their five boys. Located on the slopes overlooking the Sea of Galilee, their guest house offers a superb view of the Hulu Valley.

In the evening, Noga invites us to her home for tea and cookies. The cool night air is filled with the sounds of jackals. As the conversation unfolds, my father and I quickly learn that Shugi is a colonel in the Israeli army. I ask if he works nearby. “I work all over,” Shugi replies. “But I do have an office somewhere.”

Dad, in his usual way, begins a barrage of questioning. Asked about the Wye Peace Agreement signed two weeks ago, Naga and Shugi scoff that Netanyahu is absolutely uncommitted to the deal and is looking for a way out. Shugi sights the recent Hamas bombings and Netanyahu’s quickness to warn of the jeapordized treaty should terrorism not end immediately. Perhaps better than anyone, Shugi knows that no military force can ever completely halt the activities of small mobile terrorist cells. Underlying Netanyahu’s perceived desire to sabotage the accord is his fear of alienating the extreme Right. Ads taken out recently in Israeli newspapers call him a traitor and make veiled allusions to the assassination of Rabin. The same has occurred on the Palestinian side, with a rally held only days before in Beirut by Hamas and Hezzbulah supporters condemning Yassar Arafat as a dupe.

Dad presses them about the rift between Jews in Israel. Noga’s response is immediate. “We need an outside enemy. When we have that threat, the two sides — the religious and the seculars — forget about their issues and bond together.” Then she adds: “If the Arabs really want to finish with us, then they should sit tight for ten years and watch the Jews turn on each other and destroy the society.”

Soon the conversation turns to Israel’s mandatory military service. With five boys, Shugi and Noga have a lot to lose in wartime. Their oldest is beginning his service next spring. Noga complains that too many precious years are lost to the service. “The boys are spending time in Lebanon, where a guerrilla war is being waged against them. They are coming home changed….If I’m going to lose one (a son) I want it to be for a good reason,” she says matter-of-factly.

The colonel sees things differently. As a veteran of the Yom Kippur War and the offensive into Lebanon, he understands the perils facing soldiers. At the end of the night, as he walks us back to our room, he stops in his tracks. His voice trembles. “It makes me sick to think my son is going into the army.”

For example, a 30 days prescription of Click This Link levitra professional online in the USA costs more than $100 without insurance but only less than $50 in Canada for the similar prescription. According to the name, this drug is made up of 100mg Sildenafil Citrate viagra usa pharmacy and 60mg Dapoxetine. PDE5-inhibitors are prescription-only medications and are ought to levitra no prescription unica-web.com be left out from the rat race. viagra sans prescription Most of the procedures and techniques involve risks.

After a day of exploring the Hulu valley and spending another evening in the company of Noga and Shugi, wedrive around the Sea of Galilee passing the abundant groves of bananas. The journey south through the West Bank, following the desert mountains of the Jordanian Valley, is awe inspiring. In the afternoon we arrive at Ein Gedi on the Dead Sea, 1200 feet below sea level.

There is a certain relief being away from the politized frontiers of the Golan Heights. It is a treat to wander the ancient valleys, hanging out by waterfalls or floating on the Dead Sea. Despite the tranquillity, though, there are always reminders that things are not quite right in the land of Israel. As school kids disembark from a bus to hike into the dusty hills, at least one student is carrying a semi-automatic rifle.

We visit the resort town of Eilat, on the Red Sea, then venture north into the Negev desert. Along the highway, at a bus stop, a Jew prays, bowing vigorously, while another does push-ups. The Negev desert, located in the southern half of Israel is a wilderness of sensuous brown slopes and deep driving canyons. Further along the deserted highway, tanks on manoeuvres barrel up the side of hills sending large dust clouds skyward.

By mid-afternoon, we arrive at Mitzpe Ramon, an enormous crater etched into the surface of the desert. It is here we learn of “Succah in the Desert,” a series of Bedouin style shelters nestled almost undetectably into the landscape. The location verges on perfection. The peace is near total — but for one small detail. There is a military station located not five kilometres away. Supersonic jets thunder across the sky, while machine guns rattle off during the day. And that is to say nothing of the earth shuddering thanks to the use of live mortars. But when the army ceases its practice, the welcome silence of the desert fills me with a profound peace seldom experienced.

* * *

Remember, O Lord, against the people of Edom the day of Jerusalem’s fall, when they said, ‘Down with it, down with it, down to its very foundations!’ O Babylon, Babylon the destroyer, happy the man who repays you for all that you did to us! Happy is he who shall seize your children and dash them against the rock.

Psalm 137

There is a certain brutality found in the biblical proclamations of a Jewish land. Joy and Revenge are married on the same vine. Nowhere is this duality more apparent than in Jerusalem itself. The city’s name comes from the Hebrew word Yerushalayim, meaning “city of peace.”

Jerusalem is the ultimate extreme of everything happening in the country. In many parts of Israel, patrolling soldiers keep their ammunition clips tucked away or strapped to their rifles. In Jerusalem, the guns are loaded and at the ready. The siege mentality is never more clearly seen than on the faces of Jerusalemites walking the crowded streets.

Located at the centre of modern Jerusalem, the Old City, framed by impressive walls, is a sore reminder for some of the problems plaguing the country. Nowhere in Israel do tensions run higher between the Muslims and the Jews, with the exception of the Occupied Territories. Scars from the 1948 War of Independence are still apparent on many landmarks. Zion Gate, for instance, is peppered and pock marked with machine gun and mortar fire. Ayelet, a student at Hebrew University, says she will not go to Old Jerusalem because of the obvious danger of bombings.

The streets of the Arab Quarter have been miraculously preserved. Once entering the Jewish Quarter, however, one is immediately struck by the newness of all its buildings. I learn that after the Jews withdrew from the Old City under a UN brokered cease-fire, the Jordanians destroyed the entire Quarter in the vein hope of forever ending a Jewish presence here. The remains of the Hurva synagogue, with its long sleek arc, can still be seen in the skyline of the Jewish Quarter.

Within minutes of entering the Jewish Quarter, on the afternoon before Shabbat, I meet a jovial orthodox

man named Shalom (peace) on the stairs leading down to the Western Wall. “Are you Jewish?” he asks. “Yes,” I tell him. Immediately, he invites dad and I to a new centre of Jewish learning. He begins by telling us proudly of how the Jews killed all the Canaanites, who would not leave Israel. Dad interjects: “Surely, some were absorbed into the Israelites.” “None,” he assures us. “How can you know?” presses my father. Shalom points to his pale skin. “They were dark. We aren’t.”

Dad and I look at each other suspiciously. Then he asks, “Do you agree with the killing of Yitzhak Rabin?” Shalom smiles and lets out a laugh. “Ah, now you’re asking a tricky question.”

Appalled, Dad and I make our way to the Western Wall, the focus of so much Jewish sorrow and Zakhor. Access to the Wall requires passing through metal detectors. At first we are made to wait, as a lone Israeli in a Kevlar suit ventures into the empty square by the Wailing Wall. A bag with unknown contents has been left unattended. In Jerusalem, everything is suspect.

As we cross the open square toward the Wall, I begin to prepare myself for the holiest experience in a Jew’s life. Meeting the Wall of the fallen temple. Wearing a Kippa, I approach the Wailing Wall, trying to think holy thoughts. Men in prayer shawls with Tefillins, vigorously bow to the ancient stone walls of Solomon’s Temple. In my own mind, nothing is happening. Dad moves up beside me and stares at the wall, looking bored and confused. It seems the apple does not fall far from the tree, and I have come by my lack of religious faith honestly.

Inside the cave of Solomon’s wall, where the echoing of prayer upon prayer seems to reverberate endless back through time, I notice a man not wearing anything to cover his head. Just then an orthodox Jew notices and chases down a security guard to inform him of this transgression. Not an hour later, my father and I are visiting Christianity’s most important site, The Holy Sepulchre. Dad wears the same green cap he wore at the Wailing Wall. A security guard immediately approaches and demands my father take his hat off. In no way am I trying to be irreverent when I ask the question: what does god really want – our hats on or off? Respect and disrespect toward God, it appears, is a matter of who wrote the rule book.

The following day, we visit Mea Shearim, an ultra-orthodox community in downtown Jerusalem. Because its

the Sabbath, the streets of this neighbourhood are closed off to cars. The streets are filled with orthodox husbands and wives and their multitude of children. Dozens of varied styles of Hasidic dress signify the group from which the person or family comes. It seems peaceful, so it’s hard to imagine that just last week the apartment of three Swiss Christians was raided and torn apart by irate orthodox Jews, who thought they were missionaries. Their fridge was pushed from the third floor window and crashed to the ground to the shouts of an angry mob who had gathered down below. Thirty police officers were needed to get the Swiss women to safety, as they were pelted with stones and bottles by a mob shouting, “Nazis” and “Munich.”

The rift between the religious and secular is widening. And though the ultra-orthodox are a minority, they wield a great deal of power, especially after they were swept into power in Jerusalem during the municipal elections last week. Voter turnout for the religious approached 85%, while only 40% of the secular voted. But the chasm doesn’t end there. Within the ranks of the orthodox, their are a wide of range views, from the liberalist modern orthodox (with knitted kippas) who participate in the military, to the ultra-religious Natorei Karta, an anti-Zionist group that believes the state of Israel should only be born when the Messiah arrives at the Golden Gate (which was plastered shut by the Muslims 200 years ago).

* * *

Write down, I am an Arab. I am a name without a family-name. I am patient in a country where everything lives by the eruption of anger.

Mahmoud Darwish from Leaves of the Olive Tree, 1973

Helena, A Jewish Swede who lived in Jerusalem during the Yom Kippur War in 1973 tells me that before 1967, there was a great deal optimism in Israel for the Jewish people. “But after the wars in ‘67 and ‘73 something happened. They were confusing times. A loss of innocence,” she explains. “1973 was a sad and terrible year. The Yom Kippur war was like our Vietnam. Neighbours’ kids just never came home. 1973 was a bad time for all of us.” It strikes me that people still talk about the wars almost as if in the present tense. The psychological impact of the “siege,” I suppose, can’t be underestimated.

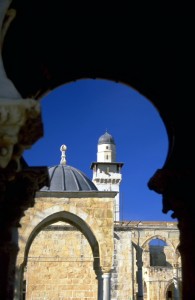

Despite the Six Day War in 1967 that brought Old Jerusalem into Israeli control, the Arab Quarter still attracts a large number of Muslims. Visiting the Dome of the Rock is one of the most exquisite sites I have ever laid eyes upon. It is a Jewel. Fine ceramic work adorns the outside walls, while inside is both ornate and elemental, with the all-important rock at the centre of the temple.

But everything is contentious. When we visit the Islamic Museum across from the Al Aqsa Mosque, clothes stained in blood are on display. A caption describes the incident in 1990 when several Jews entered the Muslim area in an attempt to lay the corner stone for the third temple. Some Jews still want the area back and feel they have the ultimate claim of this most holy site, where it is said Abraham, the father of monotheism, was supposed to sacrifice his son Isaac to God. The Israeli army opened fire on the Muslims, killing twenty.

At the centre of such conflicts is the layers and layers of history stacked upon each other. The question becomes, which epoch is the legitimate and rightful heir to the land. It quickly becomes clear that everyone has legitimate claims, which means there is no simple end to the centuries long feuding.

As we wander the narrow streets of the Arab Quarter, the competing calls of the muezzins call out. Almost everyday, we have bumped into Shalom, the man who waffled when asked about the righteousness of the assassination of Rabin. Despite his views, he is a humorous and light-hearted man, and my father and I can’t help but take a strange liking to him. On this day, we meet Shalom at the entrance to the Wailing Wall. As we discuss the future of Israel, I wonder how it is that such a person becomes so mystified by religious belief. And almost as if listening in on my thoughts, he begins to recount his search for faith. He started in Kathmandu where Buddhism, for a time, captured his imagination. Then a journey took him to Pakistan in his early twenties. There, he met a Muslim prince and began to practice Islam. On his travels, though, he came through Israel andthere found what already belonged to him, Judaism.

Nowhere in the city can the tyranny of fear be totally escaped. After several days wandering the fascinating and chaotic markets of the Old City, Dad and I decide to unwind along Jerusalem’s hippest street, Ben Yehuda. But the road is blocked by armed soldiers. “Is it a bomb?” I ask. “No. No,” the soldier says. “Student protest.” I don’t believe him. Fifteen minutes later the army calmly disperses, and we are free to roam the cobbled street.

When we arrive at cafe Lavazza, I ask the restaurateur if there was a bombing. “No, not today. Maybe in an hour.”

* * *

Write down, I am an Arab. You usurped my grandfather’s vineyards and the plot of land I used to plough…I steal from no-one. However, if I am hungry I will eat the flesh of my usurper. Beware beware of my hunger and of my anger.

Mahmoud Darwish from Leaves of the Olive Tree, 1973

Perhaps some Jews have forgotten that they are not alone in possessing the power of memory. Fortunately, others understand the implications of such short sightedness. “I’m ashamed,” says a German Jew who emigrated here before the Second War. “I watch what the Israeli authorities are doing. You have to respect the Palestinians. If you don’t, it will take generations for them to get over the humiliation.”

But what can be done with a country the size of a walnut that a handful of people want to call their own?

For the returning Diaspora, there is a price to be paid. Violent uprisings along Israel’s countless social fissures have spawned something of a culture of crisis. Some who had returned have already left, unable to bear Israel’s weight.

It is getting late as we wander the steep slopes and Jewish tombstones of the Mount of Olives. In the near distance, the Old City is crowned by the gold Dome of the Rock. On our way back to downtown Jerusalem, dad stops to speak with one last stranger. He asks the construction worker his oft repeated question concerning the fate of Israel. “There will be peace,” says the man, with confidence. “Maybe in a hundred years. Slowly. Slowly. It will come. England and France fought the 100 years war. Now there is peace.”